Milan, originally from Serbia, reflects different perspectives on his year of birth 1989 and the following process of a unifying, but also a dividing Europe. While what we called East and West was coming together, the Balkans had to struggle with war. The author describes a crack of the generation gap he found himself in and asks the question: Can people who created a ‘dream Europe’ in 1989 and those whom they created it for write their personal history together?

Children of the Revolution?

A fragment of the Berlin wall connecting this wall to the borders of the ‘fortress Europe’. (Photo: Milan)

The year of one’s birth determines the course of one’s life in more than one way. Personally, I have never regretted being born in 1989. As soon as I was old enough to receive and exchange the information with the world outside of my small town and my even smaller country, I started noticing some kind of mystical aura around that year. I somehow knew that world changed in that year.

Actually, I couldn’t have known that much. I have heard of some wall falling somewhere. I might have known an occasional hit song by Bon Jovi. I must have known the first Yugoslav Eurovision song contest winner, from that year. I started learning English very early by singing along to Sebastian’s “Under the sea” from The Little Mermaid. I think I found out much later that “The Unbearable Lightness of Being” was released in 1989, based on the famous novel of Milan Kundera. But, if I had been able to describe the life in that year, I think I might have used that exact title. Retrospectively I have to consider that this year for me, as soon as I became aware of the world around me, started to represent a landmark, a border. It was the last year when life was easy and people around me were optimistic, I thought.

Over the Rainbow

Behind that border stood something we came to call “Europe”, a magical place where optimism lived on. I realized only twenty years later how deep that

division actually was, when I was invited to a European Foundation Center conference in Berlin 2009. That autumn we were entering the White Schengen list, so a nice lady in German embassy was not quite sure what to do with my passport. She decided to give me a free visa and a free smile, none of which I was used to.

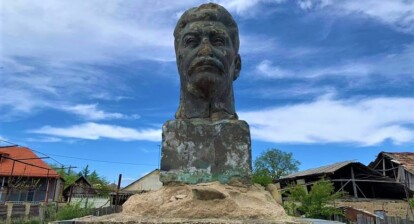

I was the youngest participant at the conference. I mentioned the fact that in last 20 years I have lived in four countries since I was born, without leaving my hometown. I felt the direct consequences of at least two ‘local’ wars and the greatest inflation in history. I tried to reconcile different images of Europe in my head: the one that celebrated in the streets of Berlin, the one that struggled hard to be allowed to witness that celebration, like in Serbia, and the one that still struggled with war at the moment, like in Georgia.

The older participants, the ones that constructed the Europe they were celebrating in those days, thanked me for bringing a fresh perspective into the discussion. It felt like they petted me on the head, but I did not have the impression they really understood what I was talking about. We had a culture gap between us, I thought back then.

Generation Y?

Last year, people from EUSTORY asked me and four other 25 year-old Europeans to answer a questionary concerning our personal views on the revolution that changed Europe in the year we were born. Reading through the answers of the others, I realized: what I felt five years ago was a generation gap, not a cultural one. Their attitudes were much more balanced. They did not actively take part in the revolution, so they could judge its results with less bias and melancholy. And their hopes about Europe were still bright, but more reserved and interwoven with skepticism. History is personal, and that is why the children of the revolution might see things more clearly than its parents.

Reflections on History and Identity

It’s been twenty years since the Dayton Agreement, which was to stop the Bosnian conflict between three different ethnic and religious groups. The new borders were marked red on the maps of Western Balkans, as if drawn with blood. The generation of my parents was torn apart, and left lost in the dark, searching for a stand-fast in new ideologies or rediscovered religions. My generation was too young to have a say in it. All we are left with today is a huge burden of layers of nationalism on our backs. We are still marked with the scarlet letter of war barbarity, and suffer the consequences of the institutional and economic crash that followed.

Twenty years after Dayton, I can say some of my best friends are Croats. I am not saying it proudly, I am not bragging. I just state it as a regular fact. With some of them I visited Split in summer 2014. I had the chance to witness the celebration of a national holiday – the anniversary of the Storm Military Operation in which hundreds of thousands of Serbs were banished. It was cheerful. There were fireworks and music. Foreigners took pictures.

National Identity and Responsibility

I felt empty. I tried to imagine, just for fun, a similar celebration in Belgrade. Despite all of my imagination, I couldn’t. It is just not possible. I see Serbian people so well trained to see any kind of expression of national identity as shameful, aggressive and forbidden. So, when Albanian football fans put up a map of Great Albania, including a great part of Serbia and its neighbouring countries during a match in Belgrade, it’s not against them that the Serbs cheer. It’s against our own prime-minister Aleksandar Vučić. However, the fact that the EU now strongly supports that prime-minister, who had an important war mongering role during the ‘90s conflicts, can be somewhat confusing to the majority of population.

With the same Croatian friends I also visited Sarajevo that autumn. I stood perplexed in the Museum of Srebrenica looking at horrors done in the name of Serbia, in my name, while I was only five and knew nothing about it. I questioned myself: Should I feel guilty? Should I apologize to somebody? How should I talk to people on the street? What would I have done if I had been there? Forgive and forget or remember and overcome?

New Challenges

Some of the answers came to me in the course of 2015. The spring was marked by the commemoration of the Srebrenica genocide, and the summer brought the waves of the refugee crisis. The cracks started to show on the face of unified and borderless Europe. People in Belgrade wanted to organize an action called 7000.That many people would have laid down in front of the Parliament in order to commemorate the victims of Srebrenica. Our pro-European prime-minister didn’t allow it. Then he went to Srebrenica and got stoned at the official commemoration.

A fragment of the Berlin wall connecting this wall to the borders of the ‘fortress Europe’. (Photo: Milan)

In the madness of migration, (mostly Central) European leaders broke a number of human rights and European values.The name of Viktor Orban will remain the symbol of violent hostility. Him and his European colleagues lifted fences and closed borders in the name of their people. After a while, those people in whose name they did it organized unofficial aid for the refugees. Serbo-Croatian border stayed closed for almost a week. Serious accusation in a war-like tone were issued by the politicians. Surprisingly, their Serbian and Croatian voters didn’t buy it this time. It left the generation Y wandering ‘why and whom are they doing it for?’

Pursuing Reconciliation

It is the mere fact that no human life can be measured, that obliges us to treat every event and every person today and in the past separately and with great care for the context they were born in and the baggage they are carrying. To talk about it – even when it hurts. To try to make balance between the burden we inherited from our parents and our need to get rid of it. When I speak to my ex-compatriots and present day neighbors of my age, it seems that this incredible lightness is attainable. That one day we can both make and write our history together. That in the future our histories can be personal and common at the same time. I hope that next generation will proudly carry the name of the children of that evolution.

“Working as an editor on HC was like feeling the pulse of Europe and rafting down its bloodstream.”

Vida Pluym

Zdravo Milan!

I can totally agree with your article. I am born in Croatia but I’ve been living in Germany since I was 3 years old. I can really identify myself with your article even if I’m born in the end of the 90’s. Why can’t we overcome these differencies and conflicts and build a new future? I enjoyed reading your article very much! True words were there.

Sincerely Vida