It was one of the biggest pandemics of all time. It is said to have killed millions by spreading on all inhabited continents within just one year – the Spanish flu caused fear and despair all over the world. But how is it perceived today, 100 years after the big catastrophe? And why is it called ,Spanish’? To find answers, our author Phillip spoke with three young Spanish students, Isabel, Elena and Yolanda, about the pandemic, its name and today’s memorial.

Pseudo-influenza. True influenza. Soldier of Napoleon. Man hu (Hebrew: What is it?). Illness eleven. Bolshevik disease. Sumo flu. Brazilian flu. German flu.

The deadliest pandemic of modern times had many names, although to this day only one name survived in the western world – Spanish flu. These two little words are the internationally understandable designation for a virus which overran the earth in three big waves between 1918 and 1919. Although the exact number of victims can only be guessed, it’s said to have killed 50 or even up to 100 million humans. In other words, ,Spanish flu’ is the term for one of humanities biggest catastrophes.

“The ,Spanish’ flu Wasn’t Only Spanish!”

Elena (21) from Seville. (Photo: Private)

But if there were so many words for the flu, why is it called ,Spanish’ today? When Isabel, Elena and Yolanda were talking about this topic, they were sad, frustrated, one even a bit angry. The Spanish Flu is not called Spanish, because of its origin. In fact, Spain wasn’t even one of the regions the pandemic broke out in first place. But, as Elena explained me: “Since the first world war was in course during this pandemic, the information about how the virus affected the involved countries was hidden there, but the ,Spanish’ flu wasn’t only Spanish.”

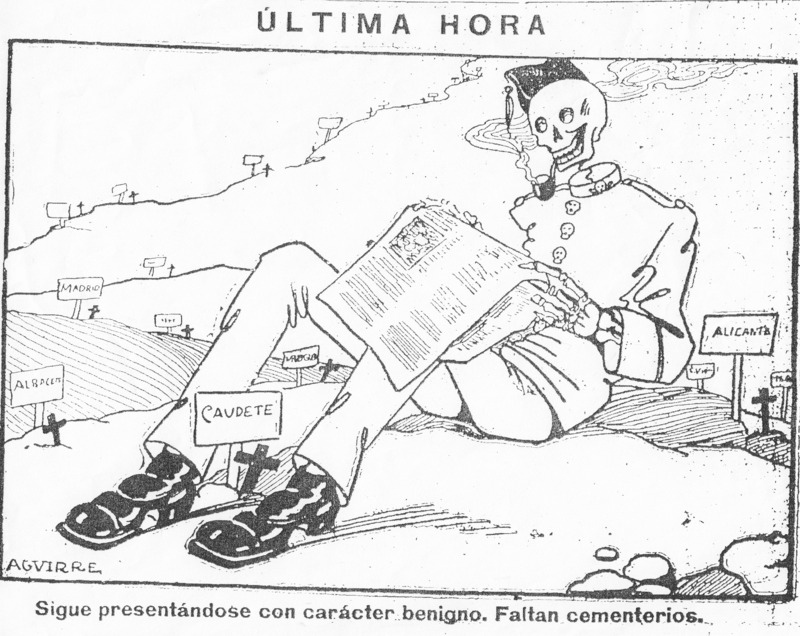

The reasons behind naming it so have a very rational core. After all, the Allied as well as the Central Powers were afraid to undermine their war efforts if they would admit that hundreds of thousands of soldiers were put out of action in summer 1918. French doctors used the cryptically designation ,illness eleven’ to avoid public panic because of the influenza. In contrast, the neutral Spain had no such reason to cover a pandemic, which infected at that time already two thirds of Madrid’s inhabitants. Although the flu reached both France and the USA before the Hispanic Peninsula, the first news about the deadly disease spread from Spain – thus, the term ,Spanish flu’ was coined.

Spanish flu and ‘Leyenda Negra’?

Isabel (21) from Écija, near Seville. (Photo: Private)

A name that still leads to unpleasant thoughts today. For example, Isabel fears that “it is possible to think that it is a country’s own virus, so foreign people have to be vaccinated when they come to Spain.” Back in 1918, many Spaniards in this more nationalistic time felt even worse. Some compared the situation to the ,Leyenda negra’ (Black legend), a propaganda myth from the 16th century which should make the Spanish Conquistadors look even more cruel and bloodthirsty than they already were.

It is therefore not surprising that the flu initially had a different name in Spain. As Elena mentions, the ,Soldado de Nápoles’ was a catchy song from an operetta, which was famous at this time in Spain and quickly became the name of this new and mysterious illness. But seemingly not very long-lasting, since Elena, Isabel and Yolanda agree that Gripe Española is the only common term in nowadays Spain.

This is no coincidence, as the three also see little public interest in the anniversary of the great pandemic in Spain. According to the history journalist Laura Spinney, it is an international phenomenon that the Spanish flu, despite its horrifying outcome at the beginning of the last century, left little mark on the collective memory. Above all, she states that there are very few public places of remembrance for this catastrophe. The survivors of the pandemic, so it seems, just wanted to forget the shock as soon as possible.

Remembrance of the flu?

Yolanda (25) from Valencia. (Photo: Private)

This has consequences until today, as Isabel mentions: “It is not a topic usually discussed in high school classes – I have never heard about it even in history classes – and it is not a term that appears in conversations, either in our homes or in any other situation. There are also no news or documentaries about the Spanish flu on TV, and our grandparents and parents don´t know about it either.” Here, Yolanda disagrees: “older people of around 60 years or more probably heard something about it from their parents, as my mother did, so they know roughly what happened”. Yolanda also mentioned that she learned briefly about the Spanish flu in school.

Moreover, today’s perception of the Spanish flu was strongly influenced by the later course of the 20th century. Because, as Yolanda explained to me, “some years after the Spanish flu, the civil war led to a dictatorship for 40 years. In Spain it is difficult to talk about this time, for example I have parents which lived during the dictatorship. This period has been invisibilized in Spain´s society for years.” The many catastrophes of the last century seem to overlay the Spanish flu until today.

Further Reading

Laura Spinney, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World, Jonathan Cape 2017.