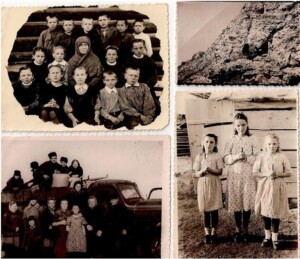

Left: Tandem partners Rasa (Lithuania) and Agnija (Latvia), August 2015 in Berlin. Photo: Agency for Historical, Civic and Media Education, Berlin; Right: A school class of deported children in the Irkutsk oblast, Siberia – nine of them were Lithuanians. Source: Private courtesy of Valerija.

Latvian and Lithuanian children being exposed to Siberia

“One after another crammed convoy moved eastward, transporting great masses of people, most of them would never have the chance to return.” This is not the beginning of a fiction novel, but an unfortunate turning point in the lives of many children living in Lithuania, Latvia or Estonia. 1940 marks not only the first Soviet occupation of the Baltic States (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), but also the beginning of repressions aimed at the local population, which included mass arrests, surveillance and deportations.

Caption: People who were deported to Soviet Gulags between 1940 and 1949. The top left: 4th graders’ class in Siberia; 9 pupils in this class were Lithuanians. The top right: Deportees on the mountain rocks near Uzkyj Lug village. The bottom left: Kazlauskai family is leaving to go back to Lithuania in 1958. The bottom right: Girls are having their first communion in the exile. Source: Courtesy of Valerija

The exact number of deported people is unknown

The first wave of deportations began on the night from 13th to 14th of June 1941, the second biggest wave of deportation took place in 1949. Thousands of families were evicted from their homes. The life stories and the biographies of children, who witnessed and survived the deportations allow us to step in their shoes and walk together with them through their lives. Children’s lives were drastically changed – they lost their friends and family members, their education was interrupted and substituted with working in the farms and fields.

Deported without an explanation

The accusations behind the deportations varied. Families were selected based on their social status. The first wave mainly impacted members of the intelligentsia – teachers, politicians and state officers. In the later years, people could be deported for very trivial reasons, like owning too much land or belonging to certain associations. Others would be deported for anti-Soviet ideas, agitation and resistance. One Latvian family was deported due to a mistake. The father repeatedly sent letters to Moscow inquiring about the reason behind their deportation; after the 3rd time, he got the answer that they were accidentally deported instead of another family. Nevertheless, the family was not released from exile.

Barracks, wooden yurts, shelters – would you call this a home?

Barracks, wooden yurts, shelters – would you call this a home?

Usually the deportees were not facilitated with decent housing. Their new home would not have the necessary appliances, no heating and quite commonly would leak through the ceiling or have its walls frozen. Valerija Kazlauskaitė–Jokubauskienė experienced such a “new home.” She was deported at the age of five, together with her mother and five siblings. They were accommodated in a stable together with two other families and would separate their space from the others with blankets. The windows would be covered with several centimetres of ice. That was the beginning of their life in Siberia.

Alone in the snow

The deportees were assigned with various tasks and children were not an exception. Ausma Melbārde was deported from her home in Latvia in 1949 and was one of the thousands of children who were assigned to tough labour. In winter, every child who went to school had to prepare twelve stacks of firewood – they had to saw off, to chop and to heap the firewood in the forest. In summer, children had to herd pigs, to weed the furrows of flax in the fields; in autumn, they had to pick up and bind sheaves. After the harvest, children had to walk around the field and glean up spikes of wheat. In the evening guards, checked if they didn’t keep grains in their pockets, but usually they ate them in the field secretly. Irena Saulutė Špakauskienė, who was deported to the Laptev Sea, recalls that the little ones had to work twelve hours during the winter and 14 hours a day during the summer.

More detailed information about the fates of the people mentioned in this article you can find in the additional files.

Educated or not educated?

Children were unable to attend school due to many various reasons. A major factor was lack of school appliances and the language barrier; however the children would quickly learn the Russian language and master its difficult grammar.

Commentary of Rasa

A lot is done to commemorate the deportations in Lithuania, however, more efforts should be made to get this history to a broader, international stage. The first time I have visited the Lithuanian Union of Political Prisoners and Deportees, which unites the ex-deportees, I was pleasantly surprised by those friendly and kind hearted people. All of them were children during the Second World War. They willingly shared their stories and told me more about what they do now. They actively participate in the society, visit schools, organise gatherings and take care of the deportees’ cemetery. Despite the hardships they had to go through they look forward. They are like flowers that survived the harshest frost, but still managed to blossom.

Rasa

Rasa

born in 1993, after finishing high school in Lithuania, Rasa is now living in London, studying History and Anthropology. Rasa enjoys travelling, reading and making new friends all around the world.

Commentary of Agnija

The project made me adopt another perspective on WWII. Usually, “Children of war” is a neglected historical topic. While reading the life stories, biographies of children of war and interviewing the victims I felt their affliction living in the hunger, without food and water, suffering unendurable diseases, deaths of close relatives, fear and terror. Do children deserve to suffer such horror? This chapter of history should always be remembered because this knowledge might help us to understand and to react to current political situations.

Agnija

born in 1995 in Latvia, Agnija studies medicine in Riga.