On the evening of the 24th of July 2011 20 young Europeans met in Madrid in order to discuss „EXILE” in Europe. But we won’t be the first ones as Laura from Latvia found out:

About 30 years ago Madrid had already been a meeting point for quite a few young Europeans interested in the same phenomenon armed with a strong and clear agenda – to focus the media attention on the issue that has made those young people exilees. They had come to protest against the occupation of Latvia by the Soviet Union.

One of them was Anna Muhka, a marketing specialist[1] and a daughter of Latvian exilees who kindly agreed to meet me for a talk on a subject that has clearly made a huge impact on her life.

One of them was Anna Muhka, a marketing specialist[1] and a daughter of Latvian exilees who kindly agreed to meet me for a talk on a subject that has clearly made a huge impact on her life.

The exile story of her family in a way is and is not typical. They were forced to stay in exile but it wasn’t a conscious decision for them to leave Latvia in the first place. Her father was in the Latvian legion (which young Latvians were forced to join) and her mother migrated with her workplace in midst of all the chaos. For some of her father’s family members the story was different – they left Latvia purposefully on a boat to cross the Baltic sea in order to reach Gotland (a Swedish island). However, it seemed an obvious choice for them to stay abroad. Her grandfather was in the deportations list of Soviet government as before the war he had been a judge of court martial in 1930’s and his family most likely would have been deported to Siberia as well.

Anna Muhka was born in 1956 after her family had already settled in Sweden; but first were the refugee camps in Germany. Her mother was in one camp and her father – in another… They had met during the war and she searched for him there. As Anna explains – people were just very happy to be alive and they were willing to enjoy life and love. When she looks at the pictures of her parents’ youth in the refugee camp she doesn’t see people being depressed about all the hardships they have witnessed during the war. She sees people happily enjoying themselves. The start of a life in a new country was quite similar everywhere. They all started from the lowest positions and least paid jobs but ended up making great careers. However, it took time and the living conditions those first years were definitely not very good.

Why Sweden? It wasn’t a very popular choice. First of all there was quite a lot of prejudice after Sweden had deported some German legion members to the USSR. Secondly, straight after the war Sweden generally wasn’t the most welcoming country. Not even close to the present model of Sweden. Refugees wanted to get out of Germany which was torn down. They thought that after losing their own countries they might as well choose living in a country which wasn’t affected by war and felt safe. Only the older people, mothers with young children and the sick stayed in Germany. Others went through screenings, waiting for some country to „let them in”. Of course, the most wanted to follow the American dream and leave for the USA but they needed to be healthy and prove that they hadn’t committed any war crimes. Canada was also widely popular among exilees. The UK only chose the strongest for work in coal mines or those who would benefit the country because of their professions – doctors for example. Some went to Australia, Venezuela and some other countries but mainly the goal was the USA. Anna’s family went to Sweden mainly because of their relatives who had come through Gotland.

The exilees’ society in Sweden was different from that of anywhere else. It could be described as more snobbish and hierarchical. Anna’s parents came from different backgrounds – her father was from a wealthy family connected with the military but her mother was just a daughter of a shoe maker. If it hadn’t been for the war her parents most likely wouldn’t have met. The war destroyed any social barriers but in Sweden they become visible again. The exilees’ society in Sweden was much more hierarchical because it mostly held those exilees that directly left Latvia by boats across the Baltic sea, often the very elite of Latvia. For example, it included the family members of first president of Latvia. But it didn’t change the fact that all of them (~5000 people who had found asylum in Sweden) were connected with the slogan- „we will be home by the midsummer” and afterwards „we will be home by Christmas” and so on. Some were quick to assimilate but mostly everyone continued to live in as much Latvian way as possible… Their aim was to create their own little Latvia. Not only did they come together to celebrate Latvian holidays, they sent their kids to Latvian Saturday school, had their own church in Stockholm, had choirs, traditional dance ensembles, theatre etc. They would even publish newspapers and books. Being a Latvian did take most of the free time they had. At the same time Anna thinks that it no way stopped them from integrating in the Swedish society; having those experiences just made them have wider horizons. However, in her youth she remembers that she would quite unconsciously keep enough distance with the local boys and date Latvians instead. Her first husband was an exile Latvian and right now she is married to a Latvian she met in Latvia. She doesn’t believe that a local would be able to understand the involvement in the exilees’ society and wouldn’t feel as comfortable there, even find it boring. Long distance relationships were a typical attribute to exile Latvians. You wouldn’t want to date someone who you knew since the very childhood, but thanks to the European Latvian Youth association (ELJA) they had the chance to meet every summer in congresses. They would both discuss the political issues and form friendships. She still keeps the letters which was the only way of communication between foreigners back then. After graduating from high school in Sweden Anna made the decision to go for a year and graduate from Munster Latvian gymnasium as well. It was a completely new experience. Even if you are used to your family speaking only in Latvian, you are not used to having all your lessons in it as well. Studying and living there felt like a completely different level. Munster Latvian gymnasium was an accredited high school in Germany which served the purpose of providing exile Latvians with education in the Latvian language. Munster became a center for possibly the most dedicated and active exilees. For example, one of the most important Latvian holidays – midsummer or „Līgo” – would always be celebrated there on the 23d of June just as in Latvia even if it was a workday. In other countries people would celebrate it on the closest weekend. After the year Anna, together with her father, made a decision to study at a German university as well.

However, the time in Germany didn’t mean just economics studies – it included lots of political and culture activities as well. Apart from the youth organisation mentioned previously there were various other organisations which held the exile Latvians together. Most notably the World Federation of Free Latvians should be mentioned which even held a special information office which would monitor the lives of Soviet political dissidents and their activities and gather information about the daily life in Latvia (starting with the “russification” politics to even such things as how much public transport costs). During that time Anna also had a chance to visit Latvia for the first time in a group of other young exiled Latvians, definitely giving a hard time for those Soviet officials whose job was to look after them. They were young and rather careless, and didn’t follow the regulations laid down for their visit. They were sure that a diplomatic scandal was the last thing Soviet Union needed and nothing bad would happen. As she remembers the trip was full of contrasts but it didn’t discourage her at all.

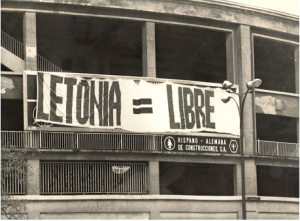

The exile organisations did a lot of work informing the world about the Soviet occupation. They always tried to attract the media attention sometimes even using activities that could be described as slightly hooligan. My interviewee was even once taken to a Spanish prison in 1980 after laying down the flag with a slogan asking for freedom in Latvia from the Santiago Barnabeu football stadium in front of Madrid’s palace of congress where at the time the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe was held. She remembers just seeing armed policemen running in the stadium’s direction and seeing helicopters flying above her head.

At the same day of another exile Latvian used a different method of protest. Māris Ķirsons, a young Latvian reverend from the USA slit his wrists so that his blood would be dripping on a Soviet flag.

At the same day of another exile Latvian used a different method of protest. Māris Ķirsons, a young Latvian reverend from the USA slit his wrists so that his blood would be dripping on a Soviet flag.

All of these activities were planned previously and included lots of preparations. There would be people in a hotel’s cellar sewing together bed sheets to create a flag, there would be someone taking pictures, and when that someone got arrested of taking pictures there would be another one doing the same who would get arrested as well.

But they achieved the goal. Her father who was at the time visiting the USA was surprised by seeing his daughter on national television there. There was even news from such exotic places as Peru that the front page of newspaper was titled „Freedom for Latvia”. The ideas were out.

Of course, it attracted the attention of the Soviet Union as well and Spain received an diplomatic nota. This diplomatic nota was probably the reason why „freeing” the protesters took so much time because generally, Anna remembers, at the time protests against communism were widely supported by the Spanish people they met. She even remembers that the highest police authority of the central prison they were brought to was soon wearing the same button asking for freedom for Latvia, too. However, the experience of being imprisoned in a cellar where you can’t understand whether it’s day or night and how long you have been there was rather frightening. After 36 hours they were freed but now she is forbidden to protest in Spain ever again.

She clearly felt passionate about the issue and explains that at the time youth in Western Europe often lacked such passion. Half-jokingly she told me a story about her German friend whom she had asked to save all the information about their protests. She remembers calling him and asking what he was doing afterwards to which her friend had answered – protesting against nuclear energy. But Joachim- since when are you interested in nuclear energy? Well, I also want to protest against something- had been his answer.

Of course it was a great celebration for all exile Latvians to witness Latvia become independent again. They even bought special radio devices to follow the counting of votes on the declaration of independence on the 4th May of 1990. Even more interesting is the fact that Anna Mukha was actually visiting Latvia on the 21 August of 1991 which was the day when Latvia officially regained its independence. She remembers crossing the bridge at night filled with tanks pointing their barrels towards the car she was driving in. She remembers those days as a very stressful time. It took about 4 years until Anna was able to move to Latvia permanently. She remembers that there were no legal issues, no documents to file or anything like that. She just arrived to live here. She returned because she was able to do so financially after getting a job at an international enterprise that paid salaries comparable to Western Europe. It happened more naturally than for many others and she is happy about the opportunities.

What changed in exile society after 1991? Well, Anna thinks that in a way it divided in two parts. All of them had their illusions shattered in some way after finding out that the Latvia they had learnt about in those 50 years was not the same Latvia you would see nowadays. The language had changed and the lifestyles of people as well. Some of them couldn’t approve of the reality but some felt that there was a place for them here anyways. She sees her upbringing as beneficial in many ways – it’s not just about the language skills but also about tolerance and democratic society values and practices that seem self-evident for her but sometimes are forgotten by locals because of their Soviet upbringing.

However, Anna sees a progress that has been made since 90’s not only in economics but in the culture of people as well. There are still some things that amaze her – “why don’t people greet each other?” What I would describe as typical shyness on behalf of the locals[2] to her seems rude. But generally, I feel like Anna’s idea of Latvia and Europe is very similar to mine. And it could be described with the fact that we were both born in an independent country being able to obtain any information we wish freely and communicate with other Europeans whenever we wish. And for that we are both grateful.

[1] In 2014 Riga is going to be an European Capital of Culture and Anna Muhka is currently working on promoting it both to tourists and Rigans themselves. As she describes it: „It’s an interesting project not only to promote Riga to tourists but make the locals proud of the city they live in as well.

[2] The term „locals” in comparison to her as coming from a different background is to be used loosely. As Anna describes she is a Latvia Latvian and not an exile Latvian anymore.

[1] In 2014 Riga is going to be an European Capital of Culture and Anna Muhka is currently working on promoting it both to tourists and Rigans themselves. As she describes it: „It’s an interesting project not only to promote Riga to tourists but make the locals proud of the city they live in as well.

[2] The term „locals” in comparison to her as coming from a different background is to be used loosely. As Anna describes she is a Latvia Latvian and not an exile Latvian anymore.